COLLOQUE LINGUA: l’IUFM de Bourgogne

7 au 9 Ávril

2003 à DIJON

PROMOUVOIR

L’APPRENTISSAGE DES LANGUES VIVANTES DE L’EUROPE : POLITIQUES ET METHODOLOGIES

Paper: HelloNet: Hellenic Enjoyable Language Learning on the

Net http://hellonet.teithe.gr

By: Ms. Afrodite

Bousoulenga, BA. MA.

HelloNET project

http://hellonet.teithe.gr

e-mail: afrobous@hotmail.com

The project HELLONET- Hellenic

Enjoyable Language Learning on the Net- http://hellonet.teithe.gr is a

three-year research project co-ordinated by the Technological Educational

Institute of Thessaloniki, Greece and developed with the support of the

Commission of the European Union within

the framework of the Lingua programme.

The aim of the project is a two-fold one.

The project is building the HELLO Net

website in order to provide:

a)

on-line distance learning

educational material for the teaching of Greek to university students; a multimedia

intensive course (with text, audio, video), video conferencing and other

materials supported by web-based services in a user-friendly environment.

b)

web-based extensive services with information about Greek

institutions and various useful links.

The target population for this project is European university mobility students who plan to take part of their studies in a Greek institution. The number of Erasmus students in Greek institutions is small, one of the drawbacks being language barriers. The project’s outputs aim to facilitate those incoming students to smoothly integrate in the Greek academic and social life and raise awareness of the Greek culture. It will also help staff who is involved in monitoring mobility programs.

The institutions

involved in HelloNet project are:

Technological

Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, GR (the co-ordinating institution),

Technological Educational Institute of Athens, GR, Universiteit Gent, BE,

Universite de Liege, BE, Leader, Lingua Formazione Comunicazione

Interculturale, IT, Sociedade da Lingua Portugesa, PT, Institut Universitaire

de Formation des Maîtres de Bourgogne, FR, Institut des Sciences et

Techniques des Aliments de Bordeaux, FR, Universidad Politecnica de Valencia, ES

and A. Amanatidou O.E. Grafikes Tehnes, GR.

1.

Introduction

Education traditionally involves

a teacher delivering information to students in the same room at the same time.

However, as we move into the new millennium, enabled by recent technological

developments in communications technologies, new forms of learning are

currently emerging and have become part of the educational landscape (Harasim

1993). More specifically, there exists an education form where teachers and

learners can choose the method of teaching that suits them best and where the

same location is not as important to the learning process; this is the

interactive classroom for distance education, a place tailored to specific

needs which makes extensive use of information and communications technologies.

The case of distance education lacks the physical presence of the teacher whose

absence is what distinguishes, as mentioned above, this form of learning from

the traditional one. However, the physical absence does not imply that there

exists no contact between tutors and students. Technological developments have

enabled tutors to communicate with each other in other ways, i.e. electronic

mail and computer conferencing. Another distinguishing point about distance

education is that learning materials are specially designed and developed for

use by distance learners. Those materials have features as clearly stated

objectives, advice about how to study and make use of the reference materials,

meaningful input and helpful examples (Hegarty, M., Phelan, A. & Kilbride

L. eds.1998).

In the present case, HelloNet is developing

Greek language teaching materials based on principles for language teaching and

on proposals for developing multimedia, grounded in SLA research (Chapelle,

1998). The material is aimed at

developing language skills of listening comprehension, reading and writing and

the level targeted can be estimated as beginners.

2. Presentation

The course will consist of 21 units; one

introductory, 16 basic and 4 revision ones. There is support in five different

languages, which are: English, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and French. Before

moving on to the lessons, the user has the possibility to select his/her

language by clicking on the icon with the flag of his/her country. This means

that all units have the English, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and French

version.

The

introductory unit presents students with the Greek alphabet. The user can

navigate through it simply by clicking on the links on the left side menu. This

unit includes information about the vowels and consonants of the Greek language

and also practice exercises on them.

As for the 16

basic units, each one of them is divided in five parts; Presentation, Glossary,

Practice, Grammar and the story of a student called Carmelo.

·

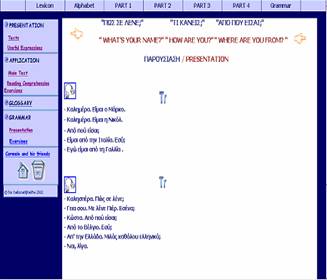

The

first part, Presentation, includes ‘Texts’ presenting a specific

communicative situation. It also includes ‘Useful expressions’ of the

same situation. It is important that the vocabulary and expressions of the

‘Texts’ are used in this part. The input of ‘Useful expressions’ should be

studied but not necessarily used.

·

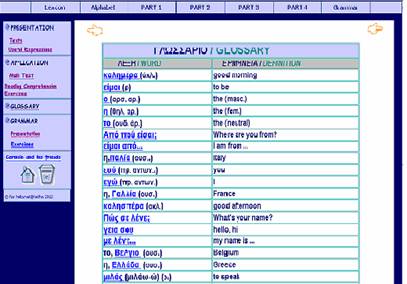

The

second part is the Glossary. It includes every single word and

expression of the ‘Texts’ translated in each respective language.

·

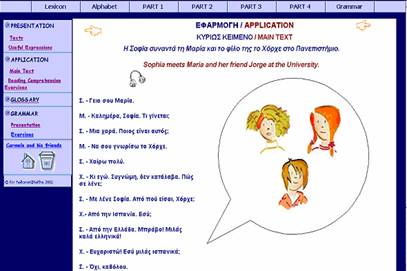

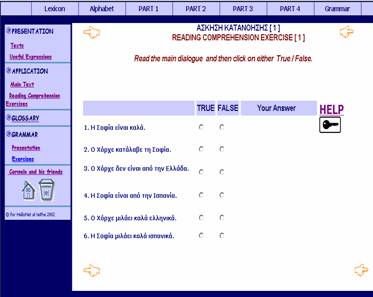

The

third is the part of Practice. It includes a ‘Main Text’ followed by

‘Reading Comprehension Exercises’ where the user practices comprehension of the

‘Main Text’.

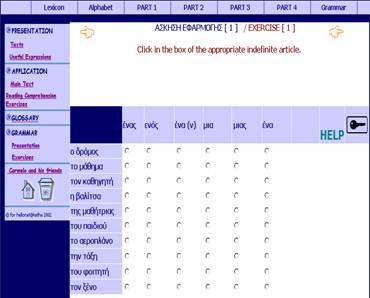

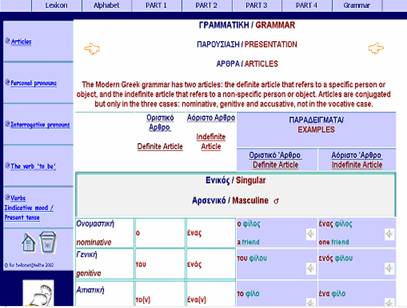

The fourth part is the presentation of the Grammar.

It is divided in the part of the Theory and that of Practice exercises. The

Theory part presents meaningful input and not just grammatical rules. In this

part Athena- the Goddess of wisdom is introduced. She makes things

easier to understand when it comes to grammar of the Greek language.

·

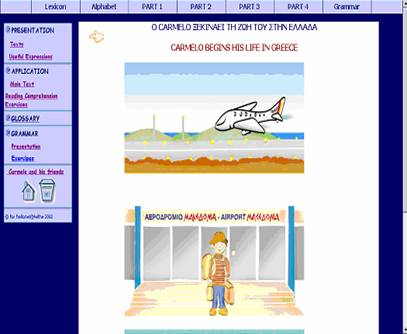

The

last part of the units gives the user the opportunity to follow the story of

our hero, Carmelo, a young student from Spain who comes to Greece as a

mobility student just like our user! Carmelo has to deal with difficult

situations and problems but finally he pulls through and has a wonderful time.

The course also provides reference materials,

a lexicon and grammar reference. The lexicon will contain all

lexical units with their definitions in all five languages. The grammar

reference will include all grammatical phenomena that the user will meet in the

different units.

3.

Pedagogical

and didactic approaches

The employment of computers in

education and research has become a reality and numerous investigations have

been conducted examining the educational potential of CALL and how much

students gain linguistically from working on it. Previous research suggests

that information and communication technologies in language teaching can

facilitate communication (Cooper & Selfe 1990), reduce anxiety (Kern, 1995;

Sullivan 1993), increase oral discussion (Pratt & Sullivan, 1994), develop

the writing/thinking connection (Warschauer, Turbee, & Roberts 1996),

facilitate social learning (Barker & Kemp, 1990), promote egalitarian class

structures (Cooper & Selfe 1990; Sproull & Kiesler 1991), enhance

student motivation (Warschauer 1996a), improve writing skills (Cohen & Riel

1989; Cononelos & Oliva 1993; Warschauer 1996b) and finally result in

higher productivity (Warschauer & Meskill 2000).

The major learning theories that have influenced so

far the production of the present software material are the Communicative

Approach and the most recent of Constructivism. Those methodologies

fall into the categories of Cognitive and Socio-cognitive Approaches both of

which have implications in the integration of technologies in the language

classroom (Warschauer 1996b).

Contemporary educators who view learning as

interactive, discursive, and situated have argued that well-designed online

environments may be particularly suited to provide the socio-cognitive support

for learning seen as fundamental to constructivist pedagogies (Lapadat 2002).

In the past, programs accommodating the Behaviourist Approach followed the

grammar-translation method- in which teachers explained grammatical rules and

students performed translations- and focused on error correction without taking

into account the mental processes that occurred in learning (Warschauer &

Meskill 2000). Exercises based on these programs worked on a ‘Wrong - Try

again’ model and did not aim at encouraging the student to communicate. In

contrast, in the case of programs influenced by the Communicative Approach we

have examples of communicative tasks that focus on the communicative aspects of

the L2, rather than its linguistic ones, and emphasise student engagement in

authentic meaningful interaction. Also, the Constructivism approach is

associated with learning and teaching that involves multiple perspectives,

authentic activities and real-world environments. Constructivism calls for the elimination

of grades and standardised testing. Instead, assessment becomes part of the

learning process so that the students start judging their own progress

(Jonassen 1995).

According to Lebow (1993), one of the 7 values of the

constructivist framework is personal autonomy, a basic element of the

Student-Centred Learning approach which argues that more effective learning is

generated when students take responsibility of their own learning as they have

different learning needs and styles and make use of various learning strategies

(Papert 1993).

We have tried to transfer the principles mentioned

above into the design of the HelloNet corpus. One way was by means of materials

which are put in the context of authentic and semi-authentic real-world based

situations supported by authentic tasks. Also, it incorporates flexible

feedback mechanisms and we wish in the future it would include a database

system for tracking user performance.

In addition to the methodological principles for

language learning and teaching, Chapelle’s (1998) ‘Seven hypotheses relevant

for developing multimedia CALL’ were seriously considered:

-

The linguistic characteristics of target language input need to be made salient for input enhancement.

-

Learners should receive help in comprehending semantic and syntactic aspects of linguistic input.

-

Learners need to have opportunities to produce language output.

-

Learners need to notice errors in their own output.

-

Learners need to correct their linguistic output.

-

Learners need to engage in target interaction whose structure can be modified fro negotiation of meaning.

-

Learners should engage in L2 tasks designed to maximise opportunities for good interaction.

4. Design Principles

Design, preparation and programming of the present

computer-based platform entailed more time in the development than the people

involved ever estimated.

There has been a clear attempt to bring

together a variety of multimedia functions in a pedagogically effective way. In

order for the material to be appropriate for language learning over distance,

the importance of interaction was primarily taken into consideration. Thus, the

core for interactive communication is a strong message and a clear

presentation (Kristof & Satran 1995).

HelloNet presents learners with a user-friendly

interface. The program is easy to navigate and provides the essential

elements of on screen help and exit features. Also, a further feature is the

presence of reference materials of grammar and a glossary. Moreover, it

provides learners with audio input recorded by native speakers in an

attempt to expose them to a variety of accents. Another positive element is the

presentation of paralinguistic features supported by appropriate

cultural information. However, we should accept the fact that being used as a material

over distance it would not be valuable for the development of oral

communication fluency.

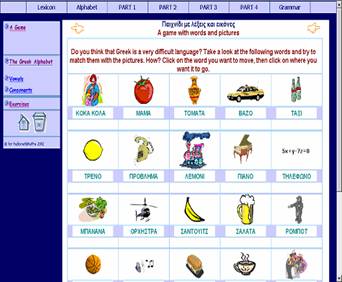

A variety of task types are used; true/false,

multiple choice, gap filling etc. Feedback is instantaneous and in

the form of green ticks and red crosses. The learner may take a look at the

answers of each task simply by clicking on the key icon and then move on to

performing the tasks for as many times as he/she pleases.

Last, the

material in an attempt to be more appealing to the target group, will include

some computer games that during the learning activities the learner can

stop, play at any time and then go back to his tasks. The theme of those games

is influenced by the Greek mythology.

5. Aims and objectives

As already mentioned, the objective of the

proposed project is to cover the needs of European University students to learn

basic Greek language communication skills before taking part in a

mobility exchange program, and to have a systematic source of information about

Greek educational institutions and the Greek academic life and culture.

The course is provided free of charge

to students of European universities as the aim of the project is mainly

educational and not commercial.

The project is developing a model

with a two-fold use: tailor-made courses to teach a European language to

mobility students and a website unique in its form whose information meets the

needs of the target group. This model when finished could be adapted to all

European languages and serve as a pattern for the production of educational

material as well as the building of similar websites.

With the integration of computer tools and

the Internet, the project promotes the acquisition of language skills, the

understanding of different cultures and strengthens the European dimension in

education. It helps to encourage educational exchanges, promotes distance

learning and the diffusion of information and uses information and

communication technologies and innovative language learning teaching tools in

the educational environment. It encourages the sharing of best practices, as it

is developed in cooperation with other partners. It produces teaching materials

for clearly defined target groups and will produce language tools that are

underrepresented in the market. The material produced helps the target group to

meet the requirements of particular situations and contexts and is generic and

not ESP. It improves the distribution and availability of products because

being available on the net, it is accessible from any computer, any time 24hrs/day.

Last but not least, the project is innovative

because:

·

it

develops teaching materials for a specific target population

·

it

uses new technologies

·

it

fills a commercial gap as there is no such material available in the market

·

it

is available and accessible 24/hrs a day from anywhere

·

it

uses a variety of teaching means

·

it

promotes one of the less taught European languages

·

it

defines new roles for teachers and students

·

it

raises cultural awareness.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, given the fact that appropriate use of

new technologies provides students with opportunities for autonomous learning

and allows for a more integration of language, content and culture (Warschauer

2000), the HelloNet project is making an attempt to promote the Greek

language. Greek, being one of the less spoken and taught European languages is

considered an obstacle to Erasmus students who might have chosen a Greek

institution for an exchange program. For this purpose, we at HelloNet are

building this site offering lessons of the Greek language supported by

information about Greece.

We are very well aware of the fact that using and

implementing information and communication technologies in language learning

demands substantial commitments of time and money and brings no guaranteed

results. However, it is our hope that the present project will meet its aims

and objectives and that we will soon welcome more European students at our

institutions.

References

Barker,

T. T., & Kemp, F. O. (1990). Network theory: A postmodern pedagogy for the

writing Classroom. In C. Handa (Ed.), Computers and community: Teaching

Composition in the twenty-first century. Portsmouth, NH: Bonyton/Cook

Publishers.

Chapelle, C. (1997). Call in the year 2000: Still in

search of research paradigms? Language Learning & Technology, 1(1),

19-43; available at http://llt.msu.edu/vol1num1/chapelle/default.html

Chapelle, C. (1998). Multimedia CALL: Lessons to be

learned from research on instructed LA. Language Learning & Technology,

2(1), 22-34; available at http://llt.msu.edu/vol2num1/article1/index.htm

Chomsky,

N. (1986). Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin and use. New York: Praeger

Cohen, M.

& Riel, M. (1989). The effect of distant audiences on students. American

Educational Research Journal, 26(2), 143-59.

Cononelos, T. & Oliva, M. (1993). Using computer

networks to enhance foreign language/culture education. Foreign Language

Annals, 26, 252-34.

Cooper,

M. M., & Selfe, C. L. (1990). Computer conferences and learning: Authority,

resistance, and internally persuasive discourse. College English, 52(8),

847-873.

Hegarty, M., Phelan, A. &

Kilbride L. (eds.) (1998). Classrooms for Distance Teaching & Learning: A

Blueprint. Leuven: Leuven University Press

Harasim, L. M. (1990). Online education: An

environment for collaboration and intellectual amplification. In L. M. Harasim

(Ed.), Online education: Perspectives on a new environment. New York:

Praeger.

Jonassen, D. (1995).

Constructivism and Computer-Mediated Communication in Distance Education. The American Journal of Distance Education.

Vol. 9, No 2.

Kern, R. (1995). Restructuring classroom interaction

with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics of language

production. Modern Language Journal, 79, 457-476.

Kristof, R. & Satran, A. (1995). Interactivity

by design: Creating & communicating with New Media. Adobe Press.

Lapadat J. C. (2002). Written

Interaction: A Key Component in Online

Learning. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol 7, No 4.

Lebow, D. (1993). Constructivist

values for systems design: Five principles toward a new mindset. Educational

Technology Research and Development: ETR&D, Vol. 41 4-16.

Little, D. (2001). Learner

autonomy and the challenge of tandem language learning via the Internet. In

Chambers, A. & Davis, G. (eds.) ICT and Language Learning: A European

Perspective. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger

Littlemore, J. (2001). Learner

autonomy, self-instruction and new technologies in language learning: Current

theory and practice in higher education in Europe.In Chambers, A. & Davis,

G. (eds.). ICT and Language Learning: A European Perspective. Lisse:

Swets & Zeitlinger

Papert, S. (1993). Situating constructionism. In Harel

& Papert S. (eds.), Constructionism. Norwood, NJ: Ablex

Pratt, E., & Sullivan, N. (1994). Comparison of

ESL writers in networked and regular classrooms. Paper presented at the 28th

Annual TESOL Convention, Baltimore, MD.

Sullivan, N. (1993). Teaching writing on a computer

network. TESOL Journal, 3(1), 34-35.

Vilmi, R.

(1998). Language Learning

over distance. In Egbert,

J. & Hanson-Smith, E. (eds.). CALL: Research, practice and critical issues.

In print for TESOL.

Warschauer

M. & Meskill, C. (2000). Technology and second language learning. In

Rosenthal, J. (ed.). Handbook of undergraduate second language education.

Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum

Warschauer, M. (1996a). Motivational aspects of

using computers for writing and communication. Honolulu: University of

Hawaii, Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center.

Warschauer, M. (1996b). Computer-assisted language

learning: An introduction. In S. Fotos (Ed.), Multimedia language teaching

(pp. 3-10). Tokyo: Logos International.

Warschauer, M., Turbee, L., & Roberts, B. (1996). Computer

learning networks and student empowerment. SYSTEM, 24(1), 1-14.

----------------------------------------

Author

Ms. Afrodite Bousoulenga, BA. MA.

HELLONET Project

http://hellonet.teithe.gr

e-mail: afrobous@hotmail.com